A love story "With Diabetes" ... like yours ... like mine

Although diabetes is a serious chronic disease that affects millions of people worldwide, I have reached the forties without knowing anyone to suffer from it.That suddenly changed a spring night last year when I met M. in a fashion store.

.Before that night I, like so many other people, only had a vague notion of what it meant to have diabetes or what it involved for the people who suffered from it, but I had the impression that it was one of many health problemsThat a long time ago they are well controlled by modern medicine, and therefore practically had not paid attention.

Although at that time I ignored it, that encounter with M. I was going to change all that radically.Diabetes would since then be a known, although distressing companion of our incipient relationship, to the point that I am currently I feel that my love is intimately linked to the disease, or rather to the strength and diligence necessary for its control, as well as the sometimes confusing balance between resignation and value, between anger and feeling of helplessness, between tenacity and abandonment, feelings that any disease triggers.

Although it would be naive to maintain that diabetes was in some way responsible for the romance that took place below, it would also be simplisticOf course, about the subsequent evolution of our relationship.That without having my ambivalent reaction to the needs that the daily care of that condition imposes.

My encounter with M. was not fortuitous.We had been enjoying an intriguing and almost anonymous written correspondence for several weeks, and our encounter that night was the first one we kept face to face.By then we knew our way of thinking about countless issues that range from love, friendship and sex, to culture, politics and spirituality, much more than most of the people even know aftermonths of intimate conversation.Paradoxically, we knew little about the daily details of each one's life.

So that from the beginning our friendship developed in the opposite direction to what is usually the usual trajectory of most friendships, which begin with the recount little by little essential and basic data of the other's life to continue deepeningThe knowledge about the way of thinking, the most intimate fears and desires of the other.

I clearly remember the moment when I discovered that M. had diabetes: after drinks and some conversation we decided.We chatted about our recent lives, of our current situation, briefly commenting on the reasons that had pushed us to look for each other.By the time we had found the restaurant and prepared to dinner, our initial fears had dissipated and the conversation had reached a relative stateJump towards that new and strange terrain of physical contact.

We examined the menu and the waiter took note.Once the wine was served, M. opened his bag and extracted a small bag, from which he took out a syringe.He removed the caperuza, adjusted the dose and proceeded to inject.All this, with the naturalness of someone who is very accustomed to doing so.When M. discovered in my face my bad concealment amazement,I immediately explained that it was diabetic.Thus my first exposure to what would end up being part of a family repertoire of daily rituals.At that time, and after the initial surprise, I quickly recorded the detail and almost as quickly as I recorded it I forgot.It seemed a simple gesture, as simple as a seemingly painless injection.It gave the feeling that it was something that did not require much attention, it was as if it were subject to a treatment that although continued, was not very important or serious.

And to some extent, from the outside it would seem that so.But only from outside.

The next contact that I remember with diabetes took place a few days after our first date, during a small party that I said on the occasion of my birthday.In it there was enough alcohol and appetizing food, both that should have made M. falling into temptation, since around midnight disappeared.I found it moments later lying on my bed with my eyes closed, pale and breathing irregularly.To the extent he explained that he was suffering hypoglycemia, probably because of excessive alcohol consumption.Suddenly the panic seized me and suddenly I also understood the seriousness of the problem that M. faced, the vulnerability and risk to which he was subject.I did what I could at that time, which of course was not much, and as I was recovering I realized that I would have to start asking questions and learning as much as I could about diabetes.

I was also aware that his state of health would constitute an inescapable part of anyone that was the relationship we maintained beyond the superficial.If we certainly intended to share our lives, diabetes could no longer remain the rest of their life as only 'their' disease.Now I needed to try to see the world with the eyes of someone like her and as others in the same situation, that is, from the perspective of who suffers a disability.A disability with its own logic, which can be relieved to some extent through the exercise of an extremely rational consciousness with respect to the body itself, with a constant surveillance of its physical state at all times.

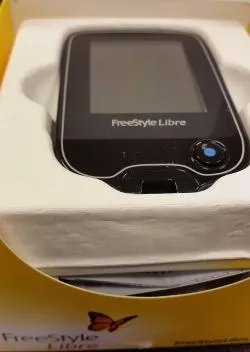

Many of the daily rituals that anyone without diabetes or thinks, or who carries out automatically or with a minimum of attention, are activities that require a very careful reflection by those who suffer diabetes.Especially as regards the diet.I mean that people with diabetes must continually make decisions about activities that, although the most basic, are those on which their own life depends.The delivery they must show to carry out this endless task is total, since the risks they run are very serious.For any activity they undertake, they must frequently monitor blood glucose levels and act accordingly.Obviously the single possibility of carrying out these controls, the fact that they have the technology that allows this surveillance of glucose rates and the self -administration of insulin is a recent privilege, is something that all diabetics should beaware and what they should be grateful.

This need to maintain attention, this constant alert with respect to the state of the body, these continuous adjustments in the diet, this permanent perception and sensitivity with respect to the physical state of your body can no longer influence the character.Every time a person with diabetes is measured by the level of blood glucose, in the background he is making an existential decision about his desire to live, about his resolution to challenge a disease.The person with diabetes must developand favor those facets of their personality that may only exist in power, facets that for those who do not have diabetes can remain latent, but that they must activate not to die.It is not the type of task that can begin and continue until it has been completed, and then rest with the feeling of satisfaction that has completed a difficult task successfully: this particular task is never complete.Any feeling of exhaustion, frustration, boredom, anguish or resistance must be set aside, at least until they have made the decision to measure, eat or inject, as the case may be, and have executed the corresponding task.It is a constant internal pressure that causes emotional demands that not even a person in intimate relationship with the diabetic person can imagine or far away.When the rest is allowed to relax, they must remain attentive.

From the past it was thought that serious diseases conferred to those suffering from a high sense of spirituality.Diseases such as tuberculosis or epilepsy were historically associated with high mental sensitivity, especially during the 19th century, when it was thought that these ailments were partly responsible for the genius of artists comochopin, Keats, Lord Byron, the brontë sisters, Dostoevsky,Van Gogh, Nietzsche or Kafka,

each of which were victims of one or the other.Likewise, certain extreme religious experiences have been related to the disease, specifically those of St. Paul and Santa Teresa to those who allegedly attributed epilepsy.That connection between suffering a certain disease and having a high sense of life and death has been thoroughly studied by the German writer Thomas Mann in his great novel "La Mágica Montaña" in which he talks about the moral and spiritual development of a young manDuring the seven years that it treated its tuberculosis in a sanatorium in the mountains of the Swiss Alps.

Diabetes shares with tuberculosis and epilepsy that quality of chronic disease.That is, it acts as a constant and intimate reminder of our mortality, of the incredible fragility of the physical structure that allows us to live, which allows us to continue living against any eventuality.That always keeping in mind the unavoidable internal fragility is different from any other kind of knowledge or certainty.This conscience represents an order of vulnerability entirely different from those dangers that stalk us to others, but presumably beyond the limits of our bodies.

The feeling of isolation that this experience must impose on the diabetic person, although both society and the patient himself overlook him, perhaps it is not always present, but does not disappear for a long time.Even love is unable to free them from their anguish, however it probably enjoys a special power to mitigate it.

Although I still do not fully understand the details of the disease or the way they affect M in the day to day, and I may never come to understand them, I have learned to recognize some of its effects and I have become accustomed to helping youTo avoid the distraction that some rituals and love efforts very often cause, remembering M frequently, for example when it is time to measure their blood glucose levels.

Sex was another facet that reserved surprises for me.I still remember the first time, while we made love M. Suddenly stopped and said: "I have to eat, now."I thought I was a joke.Soon I got used to those amazing, although brief interruptions.Even she was surprised at how much our sexual activity influenced her glucose levels, which frequently left her exhausted andwith the need for immediate ingestion of carbohydrates.As for me, I discovered that the taste and aroma that gave off his skin, his saliva when we kissed, his sweat and other sexual moods were exceptionally sweet, which excited me in a way that I had never experienced before.

Much later I learned that a German archaeologist, Georg Ebers, in 1872 discovered that in a papyrus of ancient Egypt dated 1550 B.C.A treatment for "excessive urination" was described, mention that is considered the first historical reference of diabetes.I also read that in ancient times the Hindu doctors were the first to realize that flies and ants were attracted to the sweet urine of patients with this disease, so they gave it the term of "honey urine."It was the English doctor William Cullen who in 1769 added the term 'Mellitus' - honey in Latin - to the name of diabetes.Seven years later, his colleague Matthew Dobson found that the blood and urine of people with diabetes contained high sugar levels.

Diabetes, like all serious diseases, converts the most outstanding philosophical issues into intimate concerns.While most of us work at different levels of vitality depending on our mood, our circumstances, our psychological state, and which varies as we are happy, depressed, sad or distressed, people with diabetes cannot afford to ignoreor suspend the most basic activities even for very short periods of time.They must eat regularly, even when they are depressed or simply inappropriate.They cannot allow even sadness or joy to distract them from the harsh reality of suffering from their illness.Often, when they have an episode of hypoglycemia they are not able to think clearly because their brain does not have enough glucose to function normally.In the midst of that mental confusion many times they do not realize what is happening and do not know what measures they have to take to get ahead and survive.

Love is always an adventure, and in its deepest sense it is the trip and at the same time fate.Diabetes, like so many other ailments, is not static but dynamic;It changes and evolves both on a personal level, depending on the particular circumstances of those who suffer from it - where they live, how old they are, what means they have for their treatment - as at the historical level, as progress is made in the discovery of their mechanismsand treatment methods.It would seem that we were at the gates of great advances in that sense, both to understand the genetic origins of the disease and to discover new treatments.

Meanwhile, for those of us who only awkwardly and in a way ignorant, we accompany those who suffer from the disease, love has to guide both our understanding and their courage.